For nearly three years now, I’ve been trying to engage some of my fellow Britons in meaningful debate, initially about why they’d plan to vote to leave the EU and then about why they voted to leave.

It’s been very depressing – all I’ve found is delusion, denial and the repetition of Daily Mail level mantras such as, “Were taking back control” (they tend not to do apostrophes) or, “We need to get out from under the unelected EU superstate/dictatorship“. Which is a bit rich coming from citizens of a country that, for nearly half a century, has been one of the key players in formulating the structures, processes and decisions of the EEC, the EC and now the EU.

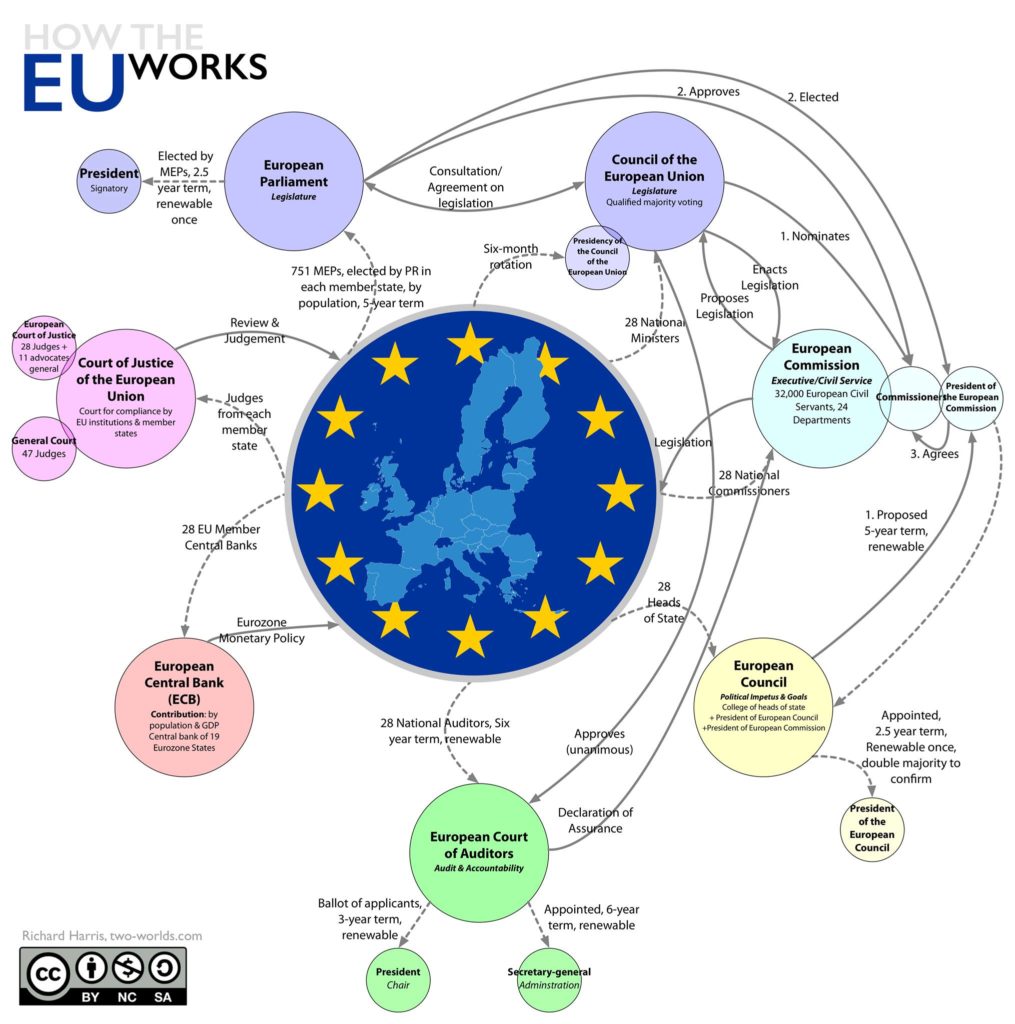

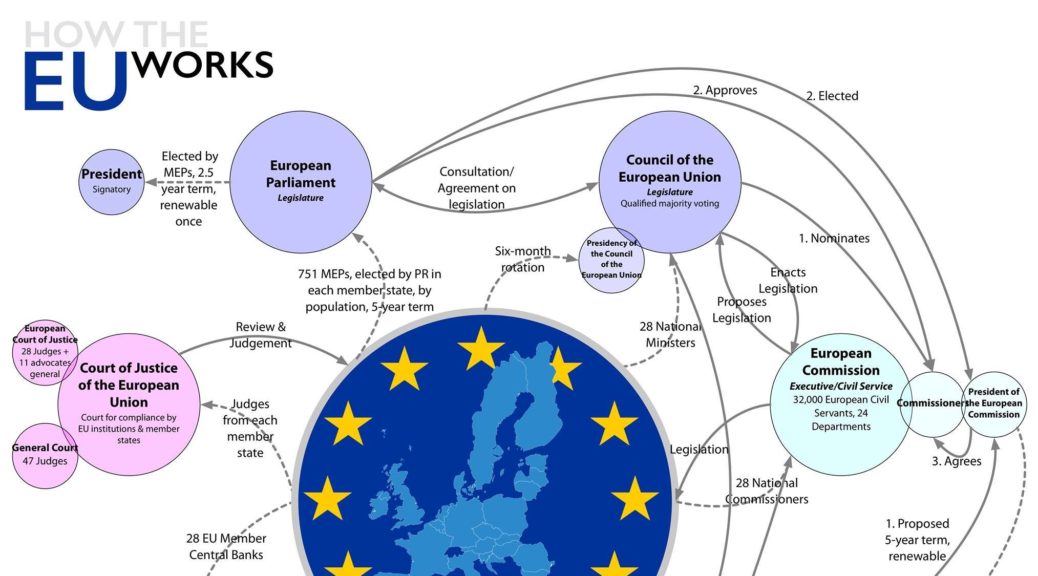

But back to that “unelected superstate“, and some more irony. Once you start digging into how each of the seven key EU institutions is governed, what you find is a pretty comprehensive set of constitutional and procedural checks and balances that all ultimately devolve back to either the governments or electorates of each member state. So what do those institutions do?

Here, I’ve tried to bring the key points together in a single infographic that focusses on demonstrating the accountability of the core institutions, both within the EU and, most particularly, to its member states. There’s way, way more detail that can be discovered from even the most cursory searches, but I hope I’ve managed to pull together the main points.

Firstly, there’s the day-to-day processes: proposing, creating, agreeing and enacting the rules. That’s the direct province of three of the bodies:

- The 751 members of the directly elected European Parliament, that discusses and agrees legislation. That’s the equivalent of our House of Commons. It’s presiding officer is a president, elected by the MEPs on a 2 1/2 year, renewable once. The current incumbent is Antonio Tajani. Heard of him? No, me neither…

- The Council of the European Union – effectively the upper chamber of the European Parliament, comprised of ministers from each of the 28 states of the EU, chaired by a presidency, a position occupied by each member state on a six-month rotating basis. Here, legislation is agreed in consultation with the European Parliament. That presidency is currently held by Romania, after the UK gave up its position in the rotation following the Brexit vote. So everything here is direct input from the member states.

- The European Commission. This is the Executive and Civil Service of the EU,with 24 departments responsible for enacting EU programmes and legislation under the direction of Council. The Commission is currently overseen by 28 commissioners – one from each member state and approved by the Parliament and by the President of the Commission, the latter directly elected by the European Parliament. The current five-year term president is Jean-Claude Juncker. Yes, we’ve heard of him.

And the massive bureaucracy that the Commission has to impose its will on nearly 600M citizens? At last count, around 32,000, including consultants and cleaners. That’s about the size of the administration of one largeish UK city.

The strategic policy for the EU is determined by the European Council (not to be, but almost invariably, confused with The Council of the European Union – there was some really bad brand definition going on there). This is the college of the heads of state of each member state, plus its appointed president (confirmed in each 2.5 year term by a double majority of the heads of state), plus the President of the European Commission. The current president is Donald Tusk.

Then you’ve got the fiscal body for the whole EU, which most particularly sets monetary policy for the 19 Eurozone states, the European Central Bank. Its membership comprises the central banks of each of the 28 member states.

Finally, there are two bodies that act as the feedback, reporting and challenge mechanism for the whole thing:

- The European Court of Auditors, whose membership is 28 national auditors, appointed for a six-year term by each member state. Its job is to unanimously approve the accounts of the EU and to provide a declaration of that assurance to the Commission. It is most notable for its ongoing refusal to sign-off the expenses of the EU Parliament and for providing the Parliament with the evidence needed to effectively force the resignation of the entire Santer Commission in 1999.

- The Court of Justice of the European Union, whose membership is judges from each member state and whose remit is to ensure compliance by both EU institutions and member states. There are two courts:

- The General Court of 47 judges, and

- The European Court of Justice (ECJ) of 28 judges (one from each member state), supported by 11 advocates general.

Yes, it is messy and complex, but that’s what happens when you have to create a system that binds together and – in theory at least – holds to account its many and diverse member states, whilst being operationally – within the limits of core alignment – agnostic to the ideologies of any incumbent national governments.

If this can help anyone at all understand the actual basis of the EU, taking them beyond the xenophobic ravings of the UK’s rabidly isolationist press, then it’s done some good.

I’m not sanguine about that though, although would love to be proved wrong: the vast majority of Leave voters that I’ve had contact with display an astonishing level of self-referential denial, often coupled with an unfortunate and reflexive tendency to start referring to the “Churchill spirit” in times of adversity.

That really does heap irony on irony when you consider Churchill’s being one of the leading visionaries and progenitors of, in his own words, “a United States of Europe“1 and that the adversity through which he led the country was the outcome of a failure to effectively integrate Europe after Word War I. Brexit, of course, is entirely self-inflicted and is borne out of another failure of integration: that of the mindset of parts of the UK both with the rest of the world and with itself.

So, to finish with some more of Churchill’s own words, “No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.“2. The EU is an excellent demonstration of just that.

And at the end of Churchill’s Zurich speech which you quote, he makes clear that he sees the UK as remaining outside of this United States of Europe.

“Great Britain, the British Commonwealth of Nations, mighty America, and I trust Soviet Russia – for then indeed all would be well – must be the friends and sponsors of the new Europe and must champion its right to live and shine.”

Also made it clear in other speeches that we are “with Europe, but not of it”. I think that’s a fairly widespread view. Supportive friendship, lots in common, yes.

He did, and that was very much the view of the time, coming from a still Imperial power that had just been on the winning side in the worst war in human history. Of course what them happened was that Europe came together, recovered and prospered, whilst Britain oversaw the dismantling of its empire, and struggled to find a place in the developing world order. For it to them join it’s peers in the then EEC was then a completely logical and rational act, one that would have happened in 1957, had Britain not been so bound up in playing poodle to the US. That in turn led to DeGaulle nixing our membership in 1967, as he felt (probably rightly) that we weren’t sufficiently committed to the European vision. The world changes, and any country that doesn’t take its opportunity to be part of a union that’s proven to be a stabilising force in a somewhat chaotic world is locking itself into a cycle of decline and self-destruction.