The Freshwater Pearl Mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) is one of the UK’s most threatened species – with Scotland alone having almost half the global population. It is a fully protected invertebrate species and is a wildlife crime priority, as illegal pearl fishing is decimating the remaining population, and dredging, forestry (whose run-off increases turbidity in the waters) and water sports all impacting its survival.

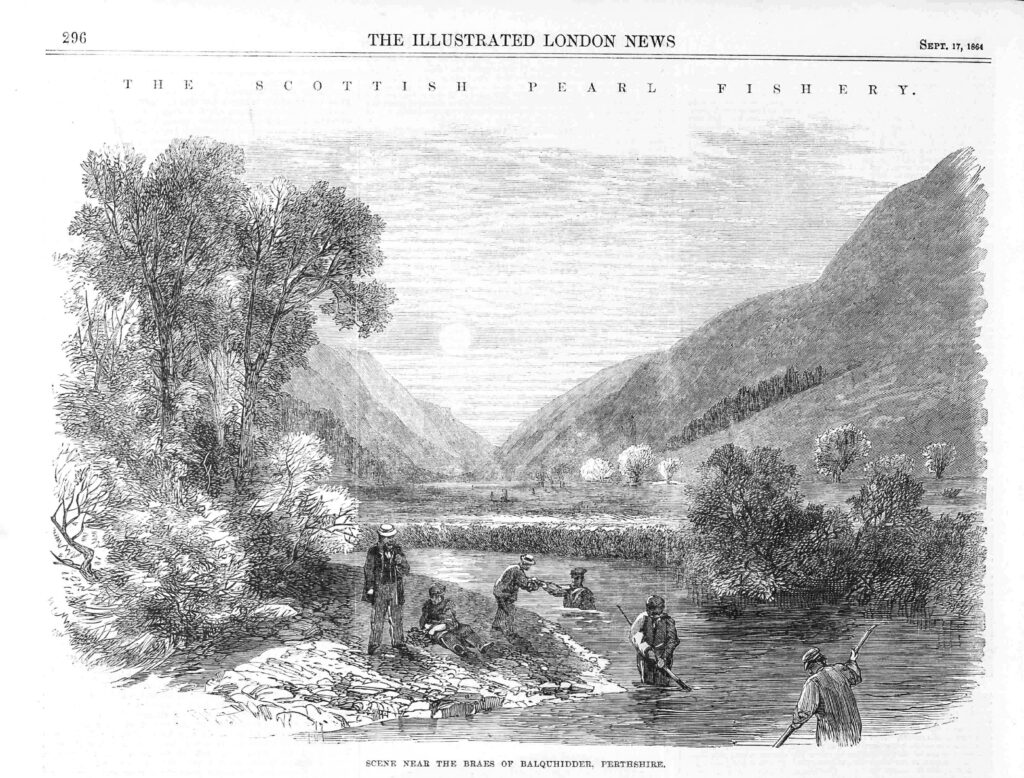

Balquhidder, historically, is an important site for the Freshwater Pearl Mussel, made famous by the well-known illustrations by Clark Stanton, for the Illustrated London News, accompanying an article published on 17 September 1864. I’ve reproduced that below (with Apple Intelligence doing a remarkably decent job of extracting the text from the images of the paper’s pages).

A recent survey has shown that the Freshwater Pearl Mussels still maintain a presence here, but that their survival may be being adversely affected by both private and commercial kayak and paddle board launching from some parts of the river system – we’re working with NatureScot and Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park to try to resolve that, but it’s a slow process. Anyway, on with the historical bit…

Illustrated London News, 17 September 1864

The pearl, one of the most beautiful of our gems, is found in a species of shellfish, which is a variety of the mussel, not an oyster, as is commonly supposed. In the Eastern seas professional divers are employed to go down into the depths in order to obtain them-a dangerous occupation, at one time only followed by condemned criminals. The best known fishery for pearls is that at Ceylon, which was at one time, in the hands of the industrious Dutch, a very lucrative concern. When our own Government took up the pearl fishery, in 1797, the annual produce was £144,000, which in the following year was increased by fifty thousand pounds, but immediately afterwards fell off, most probably from overfishing. It revived again, and in the beginning of the present century the pearl ground was leased to private adventurers at the large rent of £120,000 per annum, with the understanding that the bed, or bank, was to be divided into portions, only one of which was to be worked at a time, so that a part of the mussels might have a good rest. From various causes, however, the Ceylon fisheries have again failed, and are this year totally unproductive. But, during the past two or three summers, the old industry of pearl-seeking has been very successfully revived in Scotland, chiefly through the auspices of Mr. Moritz Unger, a dealer in gems residing in Edinburgh. That gentleman, having in the way of his trade occasionally fallen in with pearls said to be obtained in Scottish rivers, was so struck with their great beauty that he determined to set about their collection in a more systematic way.

At that time there was in Scotland but one professed fisher for pearls, who lived at Killin, and whose stock was principally bought up by the late Marquis of Breadalbane. Mr. Unger, having in view the extension of the trade, travelled over the whole country, and announced his intention of buying, at a fixed scale of prices, all the pearls he could obtain, taking possession, in the meantime, of all he could get from the peasantry at a liberal price. The consequence is that now, instead of there being but one professed pearl-seeker in Scotland, there are hundreds who stick to pearl-fishing as their sole occupation, and, being sober and industrious men, can make a good living by it. The Scottish pearls were, in the middle ages, celebrated all over Europe for their size and beauty. Just one hundred years ago, between the years 1761 and 1764, £10,000 worth of pearls were sent to London from the rivers Tay and Isla; but the trade carried on in the corresponding years of this century is far more than double that amount. Mr. Unger estimates the pearls found this summer to be of the value to the finders of about £12,000; whereas on his first tour he bought up, four years ago, all that were to be had for a sum of £40. Single specimens have recently been found worth as much as £60. From the middle of the last century till about 1860 the Scottish pearl fisheries were quite neglected, and large pearls were found only occasionally, as it were by accident, in dry seasons, when the rivers were scant of water and the mussels were, consequently, accessible without much trouble. It was left for Mr. Unger to discern the capabilities of the beautiful Scottish pearl as an ornamental gem of great value; and it is now a fact that the beautiful pink-hued pearls of our Scottish streams are admired even beyond the Oriental pearls of Ceylon. The Empress Eugénie, Queen Victoria, and other Royal ladies, as well as many of the nobility, have been making large purchases of these Scottish gems. In some rural districts, the peasantry are making their fortunes by pearl-seeking for only a few hours a day. Many of the undemonstrative weavers and cobblers, whose residence is near a pearl-producing stream, contrive, in the carly morning or after their usual day’s work, to step out and gather a few handfuls of the pearl-containing mussels, in which they are almost sure to find a few pearls of more or less value. The pearl-fisher requires no capital to set him up in his trade; he needs no costly instruments, but has only to wade into the stream, put forth his hand, and gather what he finds. Mr. Unger even provides his pearl-gatherers with a waterproof dress, so that their labour may be as little detrimental to their health as possible.

An intelligent pearl-fisher has sent to the writer the following graphic account of what he calls the ‘pearl fever’:

“For many years back the boys were in the habit of amusing themselves in the summer-time, when the water was shallow, by gathering mussels and searching them for pearls, having heard somehow that money could be obtained for them; but they often enough found that, however difficult it might be to secure the pearl, it was still more difficult to get it converted into cash, threepence, sixpence, or a shilling being the ordinary run of prices, buyers and sellers being alike ignorant of the commodity in which they were dealing. It was not till the middle of last summer (1863) that the fever of pearl-searching broke out thoroughly. The weather had been uncommonly dry for some time, and the river had in many places become extremely shallow; some of the women and children had been employing their spare time in gathering mussels and opening them, and few who had given it a trial failed to become the possessors of one or more pearls. Just then Mr. Unger made his appearance, and bought up all he could get at prices which perfectly startled the people; and, as a consequence, young and old, male and female, rushed like ducks to the water, and waded, dived, and swam till the excitement became so intense as to be called by many the ‘pearl fever.’ The banks of the river for some time presented an extraordinary scene. Here a solitary female, very lightly clad indeed, is seen wading up to the breast, and as she stoops to pick up a mussel her head is of necessity immersed in the water. Having got hold of a shell she throws it on to the opposite bank and stoops for another, and in this manner secures as many as her apron will hold, and carries them home to find that, very likely, she has more blanks than prizes among them. There, in a shallow part of the stream, a swarm of boys are trying their fortune; there is a great degree of impatience in their mode of fishing, for each shell is opened and examined so soon as it is lifted. A little above them are two scantily-clad females earnestly at work; one of them is actually stone blind, but she gropes with her feet for a shell, then picks it up with her hand, with a stout knife carefully opens it, and with her thumb feels every part of its interior. She has been pretty successful, and her tidy dress betokens the good use she makes of the proceeds of her fishing. The spectator may next pass through crowds of men, women, and boys similarly employed, where the grassy banks are reddened by the constant tread of many feet, and the smell of heaps upon heaps of putrid mussels tells the magnitude of the slaughter. The eye is then attracted by the sight of a man on crutches making for the river. He soon gets seated on the right bank of the water, where his better half, in water almost beyond her depth, is gathering from the bottom of the muddy and all but stagnant part of the river a quantity of shells for him to examine. Nor are the labours of this couple unrewarded; for, by their united exertions, they earned in a few weeks somewhat above £8, and so little idea had they of the value of the pearls, that on one occasion when they expected about fifteen shillings for a few they had dispatched to the collector, they were agreeably surprised at the receipt of three times that amount by return of post.“

It was found that the fishing was most successful where the river was deep and its motion sluggish. To get at the mussels in such places, large iron rakes, with long teeth, and handles about twenty feet in length, were procured, and by them some of the deepest parts of the river were dragged and some valuable pearls secured; many of which were disposed of at £1 each, others at 25s., and one or two at £2; while a great number ranged from 7s. 6d. to 5s. each. But by far the greater portion were either entirely useless, or on account of their smallness, bad shape, or colour were parted with for a mere trifle.

Some idea of the extent of the pearl fishery in 1863 of this one river may be gathered from the fact that Mr. Unger paid to those engaged in it a sum exceeding £150 for each month the fishing lasted; and a goodly number of pearls were disposed of to private individuals in the vicinity for their own special use, besides those that found their way into the markets. During the continuance of the fishery the general cry was that so much exposure of the body was likely to introduce a variety of diseases such as had not hitherto been known in the place; but no such effects made their appearance. And though there were exceptional cases where the extra cash (for it was like found money) obtained from the pearls was worse than wasted, there are many who can point to a new suit of clothes or a good lever watch, when asked what they have to show as the reward of the many cold drenchings they got while dredging the Doon for pearls.” A controversy has arisen as to which rivers produce the best pearls, and it has been argued that only in those rivers having their sources in a loch is a continuous supply of the pearl-mussel to be found. But it appears that very good pearls have been taken from rivers that take their rise in some little spring and gather volume of water as they flow. Many of the finest gems have been found in the Tay, the Teith, the Doon, and the Garry.

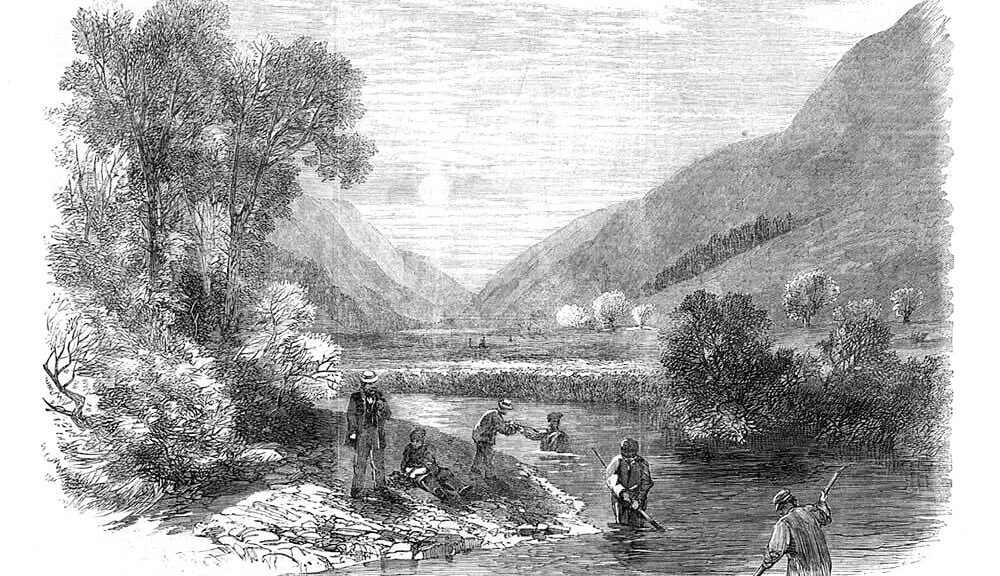

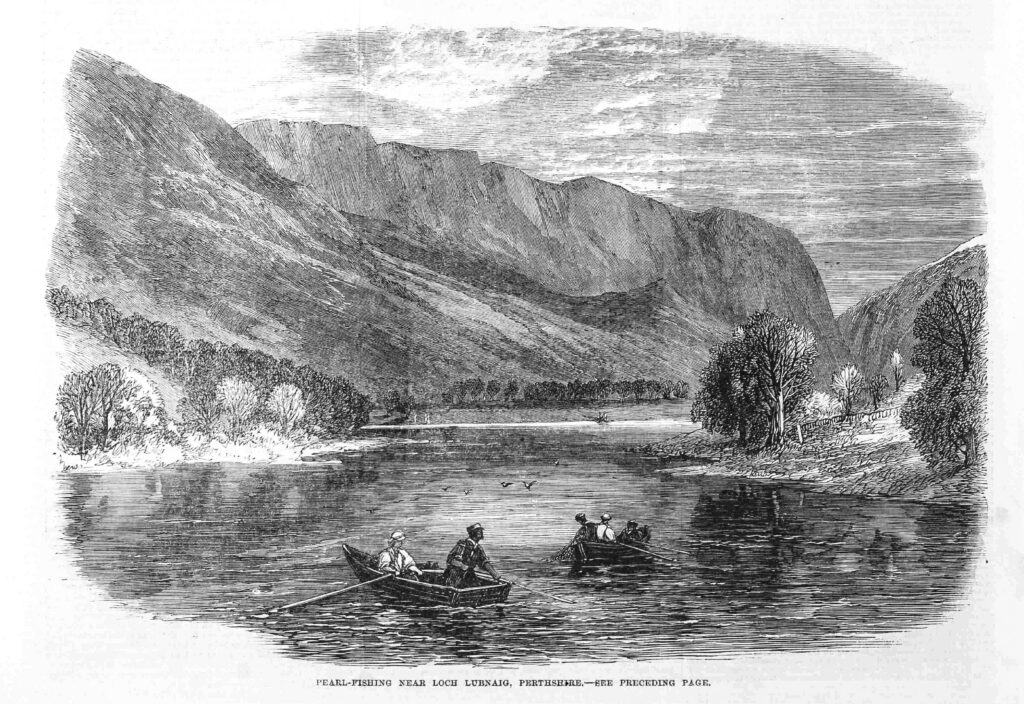

The pearl-seekers shown in our Engravings, which are from drawings by Mr. Clark Stanton, are exercising their industry near the picturesque “Braes of Balquhidder,” in Rob Roy’s country, and at the outlet from Loch Lubnaig, in the Pass of Leny. It may be observed, nevertheless, that the only rivers not flowing from a loch in which pearls are found are the Ugie, the Isla, the Don, and the Ithan. It is supposed that the lochs are the natural reservoirs of the pearl- mussel; and in support of this theory it is held that those rivers flow- ing from these large sheets of water are richer than any others. In 1860-1, when a portion of Loch Vennachar was laid dry for the purpose of building a sluice for the Glasgow Waterworks, innumerable shells were found, from which the labourers gathered a great many very fine pearls. It is known, from experiments conducted under the auspices of Mr. Unger, that Lochs Lubnaig, Earn, Tay, Rannoch, and many others further north, as also west and south, are actually teeming with shells; and it is also certain that there are many rivers in Scotland full of pearl-fish that have never been fished at all. It is said that pearls may be found in many of the Irish and Welsh rivers. The Conway was noted for them in the days of Camden. The pearl mussels are called by the Welsh “Deluge shells,” and are thought by the ignorant to have been left by the Flood. The river Irt, in Cumberland, was also at one time a famous stream for pearls; and during last century several pearls were found in the streams of Ireland, particularly in the counties of Tyrone and Donegal. We read of specimens that fetched sums varying from £4 to £80.

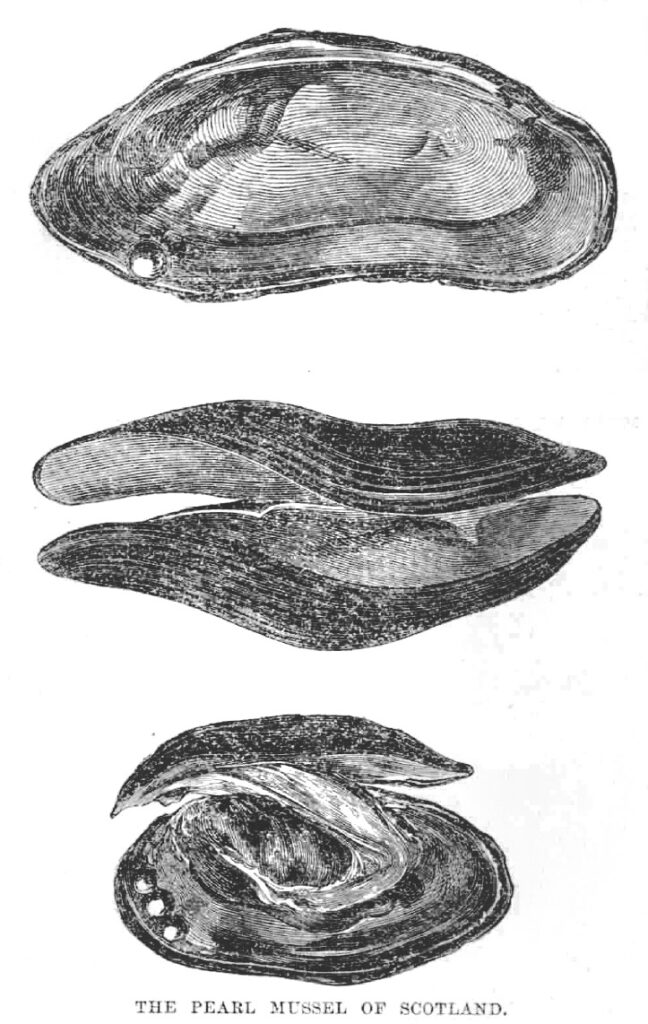

If our readers be curious to know how many shells will have to be opened before this toil is rewarded with a find of pearls, let them be told that, on the average, the searcher never opens a hundred mussels without being made happy with a few of the gems. It is remarked that they are more certain to have pearls when they are taken from the stony places of the river; thousands of mussels have been found in the sand, but these have rarely if ever contained a single pearl, whilst the shells again that are found in soft and muddy bottoms have plenty of gems, but they are poor in quality and bad in colour. No pearls are ever found in a young shell, and all such may at once be rejected. A skilful operator opens the mussel with a shell, in order to avoid scratching the pearl; the opened fish is thrown into the water and there greedily devoured by the salmon and other fish, so that those proprietors of streams who were becoming uneasy as to the effects of the pearl fishery on the salmon may set their minds at rest.

It is interesting also to note that the fame of the Scottish pearl fisheries has so extended as to bring buyers all the way from France and other Continental countries; and, as boats and dredges are now being introduced, it is thought that any moderate demand may be supplied. Great quantities of pearls have been sent to the collector through the post office.